Chronicles of a Separation

Award-winning photographer Laura Pannack on what does Brexit means for love and the exploration of the “beautiful awkwardness” of human relationships.

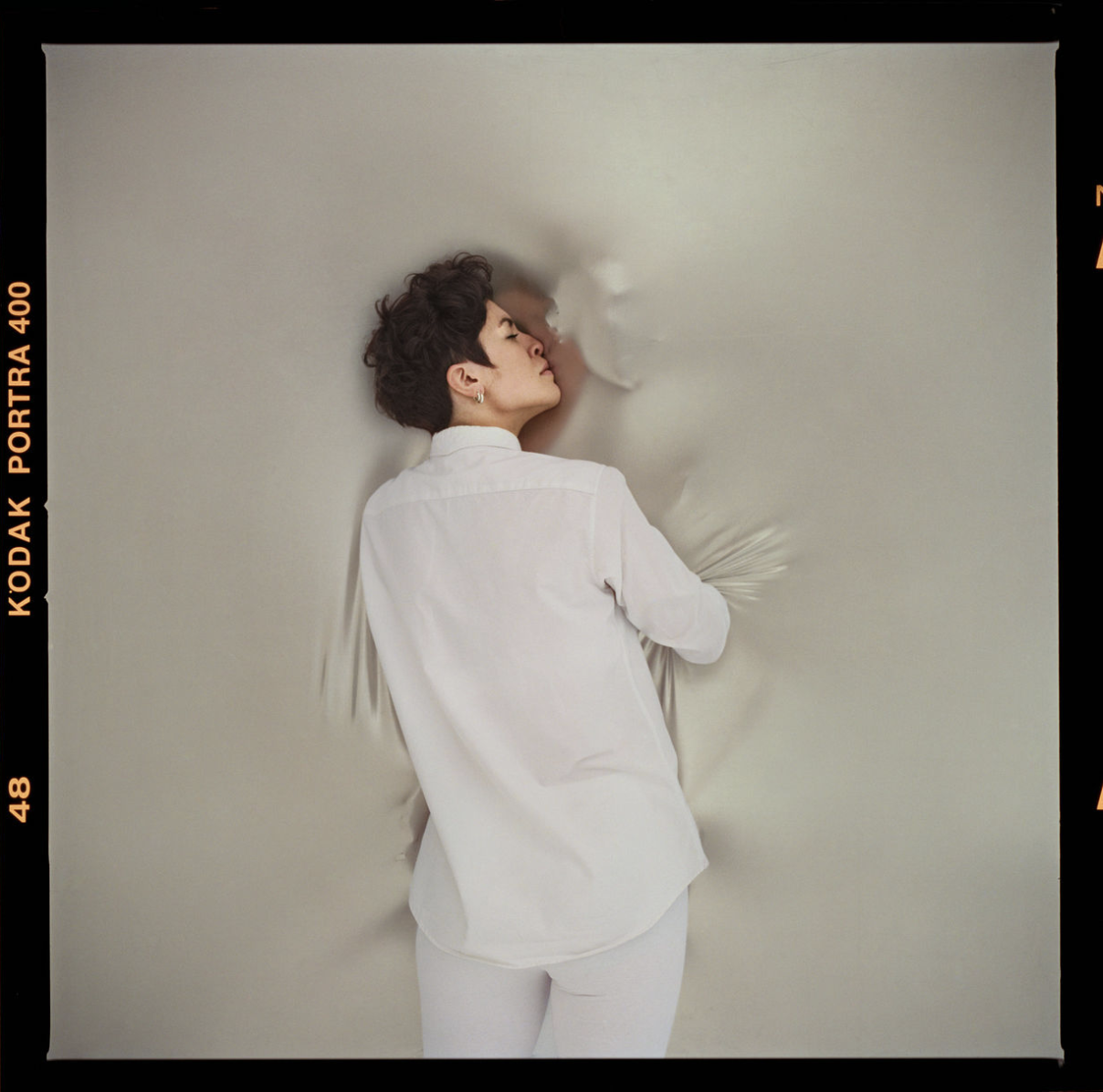

Separation series. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2018, two years after The United Kingdom voted for the first time in a referendum to leave the European Union, photographer Laura Pannack was Commissioned by the British Journal of Photography and the Affinity Photo for iPad, to explore the uncertainties and emotions felt by UK-based couples threatened by a potential separation as a consequence of the Brexit’s implementation.

Early this year, when EU rules formally ceased to apply to the UK on December 31st (right after the post-Brexit transition period), the Separation series did not only change its meaning compared to the year it was produced but it found new channels of reinterpretation. Today, Laura’s portraits enable the viewer to explore the concept of “separation” from different contexts and circumstances: from COVID-19’s social and individual repercussions to the class stratifications that separate people around the world.

For this issue, we talked with Pannack about the initial inspiration behind Separation and her exploration of the “beautiful awkwardness” of human relationships.

Separation series. Courtesy of the artist.

Georgina: How was your first approach to photography and when did you first start experimenting with portraits?

Laura: My dad is a photographer, so when I was very young, I remember I used to watch Tom and Jerry on TV in his dark room. My mother is very creative as well. I started studying painting and I hadn’t tried photography until I was on my foundation course. It was a very cliché-type of moment because a teacher that didn't like me very much told me that I was very good at it and asked me for how long I had been doing photography. I said “five minutes”. I fell in love with the process. This teacher, even though he didn’t like me, gave me the confidence that I needed to start. After that, I just became addicted to photography so I started to take pictures on a daily basis.

G: You studied a foundation course in painting at Central Saint Martins College of Art. How has this artistic discipline influenced the aesthetics and style of your current photographs?

L: A hundred percent! When I was a child, my mother used to drag me down to painting and drawing exhibitions. She loves art and I think this was a huge influence on me.

G: Relationships, intimacy, love, uncertainties and the future are some of the constant subjects that we can see personified in your work. How do you transport these feelings from your images to the viewer?

L: That’s a very good question because I think that’s the goal. For me, a successful piece is one that transports you into it. Whether it is a landscape painting or a portrait photograph. I don’t think there are any tricks. The only and very simple rule is that I have to be interested in what I am capturing. Because if I can connect with whatever I’m photographing, then I hope someone else will.

G: Of course! So I guess it’s part of your work as well to be completely involved with the subject. Is that right?

L: I think it’s imperative to form a connection and for myself and whoever I am photographing to trust one another. Sometimes this can be challenging especially if there are restrictions however I hope that I can offer direction and create an image whilst still allowing the space and freedom for the participant to collaborate and present themselves as they like. Ultimately the experience has to be a collaboration.

Young Love series. Courtesy of the artist.

G: So being comfortable is important for both, you and the people you are photographing...

L: Exactly. But you know... sometimes that awkwardness is needed. When somebody is naturally awkward, there’s tension and that could create tension in a shot. Tension is a lot of what my work is about. Love can be really awkward and I think that is beautiful because it’s not perfect. It’s not the Hollywood kind of romance. It is like when we were young and we had our first kiss thinking “I don’t know what I’m doing”. And you know? We can all relate to that feeling.

G: When in 2016 The United Kingdom voted in a referendum to leave the European Union for the first time, the press media started to talk about the uncertainty of thousands of people in terms of work, professional opportunities, studies etc. But the love-related doubts were rarely explored. What inspired you to create the photo series Separation?

L: It was actually a commissioned work by 1854 Media and created with Affinity Photo for iPad. They approached me and asked me to shoot a series about Brexit. I showed them some tests I had been working on with couples that I wanted to develop and we combined our ideas. I wanted to strip down the complex political conversation to a basic human emotion. I wanted to allow engagement and accessibility.

I was looking into Greek mythology which became a big inspiration for this work. This is how the idea of portraying couples that could be potentially separated through Brexit was born. Because if you can’t relate to love then what can you relate to?

G: Today, I think it’s hard to see the real impact that Brexit is going to have on society in a near future. Do you think that the perception and meaning of Separation will change in a couple years?

L: Yes, I do and I think it is funny how relevant this series has become relating to COVID as well. A lot of people asked to to use these images for COVID-related subjects to portray how people have been separated after the 2020 outbreak. I think that the main aim of these series is just to strip back the topic of Brexit and bring it back down to a simple human emotion. Unfortunately, I have to say it’s TOO late now, you know? This is just a documentation of something that has already happened, a reflexion rather than a fight for a cause. But also I guess that when you are doing a project like this, it is important to step back and try to be as impartial as possible. I spoke to people that voted for Brexit and I tried to understand their causes even though I didn’t share the same point of view.

Separation series. Courtesy of the artist.

G: The first time that I saw these photos, and without knowing the context of the project, the first thing that came to my mind was the impact that the pandemic is having over the physical and even mental segregation of thousands of people around the world. Do you think that Separation could be reinterpreted depending on the viewer’s contexts and current realities?

L: As an artist, and maybe a little bit selfishly, I would hope that these series will live on for many different reasons. I imagine there will always be reasons for separation.

G: In 2015, you were invited to become a judge in the portrait category in the World Photo Press Awards in Amsterdam. What advice would you give to upcoming and young photographers who want to immerse themselves into portrait photography?

L: I think that if you have the passion for making images, the biggest key factors for me are empathy and vulnerability. I think honesty is very important because if your intentions are good, people will recognize that and they will engage and connect with you. Be clear in your intentions and just be nice!

G: You mentioned before having some Greek mythology influence in Separation. Could you share with us one of your favorite references about this topic?

L: “In the beginning, humans were androgynous. So says Aristophanes in his fantastical account of the origins of love in Plato’s Symposium. Not only did early humans have both sets of sexual organs, Aristophanes reports, but they were outfitted with two faces, four hands, and four legs. These monstrosities were very fast – moving by way of cartwheels – and they were also quite powerful. So powerful, in fact, that the gods were nervous for their dominion.

Wanting to weaken the humans, Zeus, Greek king of Gods, decided to cut each in two, and commanded his son Apollo “to turn its face…towards the wound so that each person would see that he’d been cut and keep better order.

The severed humans were a miserable lot. Finally, Zeus, moved by pity, decided to turn their sexual organs to the front, so they might achieve some satisfaction in embracing.

In the 17th century, French philosopher Blaise Pascal offered an account of the wound of our nature more in tune with secular sensibilities. He claimed that the source of our sins and vices lay in our inability to sit still, be alone with ourselves, and ponder the unknowable.

We seek out troublesome diversions like war, inebriation or gambling to preoccupy the mind and block out distressing thoughts that seep in: perhaps we are alone in the universe – perhaps we are adrift on this tiny rock, in an infinite expanse of space and time, with no friendly forces looking down on us.

The wound of our nature is the existential condition, Pascal suggests: thanks to the utter uncertainty of our situation, which no science can answer or resolve, we perpetually teeter on the brink of anxiety – or despair.”

An extract from the essay “What Plato Can Teach You About Finding a Soulmate” by Firmin DeBrabander, Professor of Philosophy, Maryland Institute College of Art.